Siloed: Art for Uncertain Times

In March, 2020, the world upended. COVID-19 quickly immobilized the urban seaboards, and fear coursed throughout the globe. In New York, we consumed news and media with great frenzy, searching for a source to unveil the secret to our survival. And if we couldn’t find medical know-how against our virulent opponent, at least we had seven hours of anesthetic reprieve watching a zookeeper and his tigers. Toilet paper, hand sanitizer, flour, and soda flew off store shelves and filled pantries. The world around us both stopped and roiled.

The Center for Latter-day Saint Arts issued a call for proposals, titled Art for Uncertain Times, in April, 2020, which was born of our desire to belong to our community in a moment of global distress. This exhibition draws from that project. The inclination to create offered tethers of hope and humanity as we clung to Georges Braque's notion that “Art is a wound turned to light.” We asked artists, scholars, and others for said illumination: How were they to process this new normal?

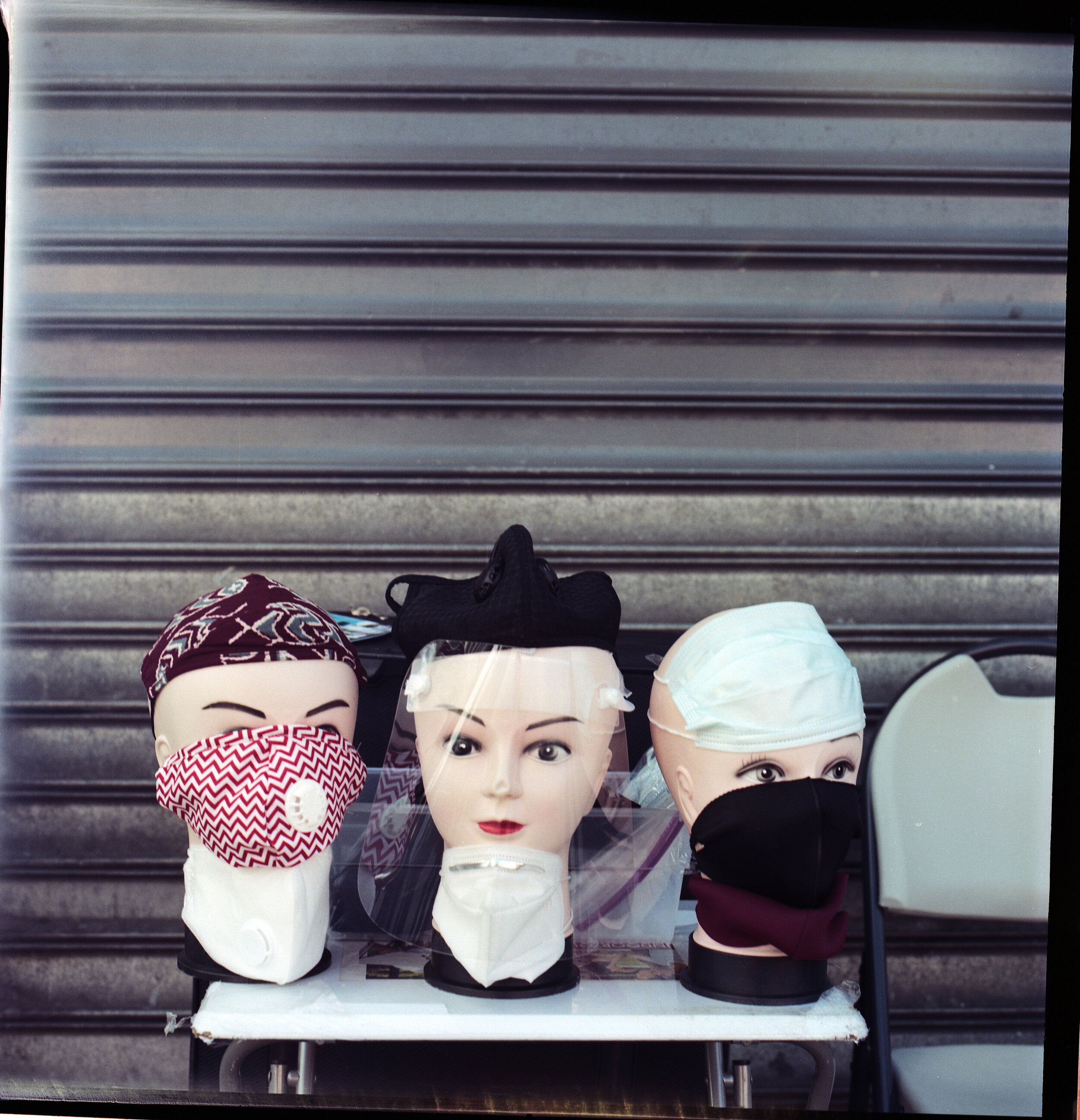

In May, 2020, fifty winners from hundreds of proposals were selected for the project. Entries came from all over the world and in multiple disciplines—from a Latino poet configuring eight poems to serve as a liturgical menorah symbol; to a Brooklyn street photographer juxtaposing the preternatural quiet of a city in lockdown against the growing embers of social disquiet. The marks of light and dark can be read throughout Siloed: Art for Uncertain Times. The seen and unseen. The known and unknown.

There’s another significant layer to Siloed. The undercurrents of social unrest and critical race discourse are present, and sometimes dominate, the works. Some are an urgent response to the tragic deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor. If initial and early reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic are personal peace treaties with illness or ambiguity, later works are an engagement in heavy conversations regarding systemic racism, generational trauma, and neglect. There are stakes to living in silos, which are arrestingly questioned in this exhibition. What does it mean to belong to each other, even in isolation? And how do phantasmic forces expose inequities for BIPOC communities? Unsurprisingly, the response from young artists, ages 8-18—collected in a subsequent call known as Art for Uncertain Times: Next Generation—comprises the most insightful frame for healing from both COVID-19 and systemic racism.

What comes next? Where might we be a year from now? Siloed: Art for Uncertain Times is a record of the moment as it was lived. Sometimes, these early pandemic works are a call to action; other times they are a question mark. Nonetheless, they remind us that to understand one another in the light, we must love one another in the dark. Offering equal parts stillness and frenzy, this exhibition reaches out for personal connection amidst distinct silos of experience.

Siloed: Art for Uncertain Times is organized by Emily Larsen Doxford. This exhibition and the Art for Uncertain Times projects were made possible by the support of generous donors to the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. Graphic design for the exhibition was done by Cameron King. A special thanks to Glen Nelson, Kah Leong Poon, Jeff Larsen, Lindsay Larsen and Chase Westfall for their expertise with special projects for the exhibition.

Justin Wheatley (American, born 1980)

When Dark Clouds of Trouble Hang O’er Us (2020)

acrylic on canvas, 30 x 30 inches

The Private Collection of Cris and Janae Baird

On Wednesday morning, March 18th, 2020, a 5.7 magnitude earthquake struck Utah. Salt Lake City artist, Justin Wheatley, was quarantined at home with his wife and family when it happened. He recalls, “My responsibility as a physical and spiritual protector of my family was suddenly very real.”

When Dark Clouds of Trouble Hang O’er Us is the depiction of that experience: living through both earthquake and pandemic simultaneously. The painting operates well within Wheatley’s oeuvre, an exploration of the ironies of suburbia. Yet this work is an outlier; the viewer is invited into the interior of the home and we can peek into windows to see layers of life inside. Evidence of humanity transforms the structure from symbol or container into living embodiment.

As is true of much of Wheatley’s work, a sense of history pervades When Dark Clouds of Trouble. The connection between the past and the future is important, as are the connections he is making between life and death. What is happening outside the home is as significant as what is happening inside. Here, a vibrant red stripe above the roof’s pitch references the Passover. This ancient ritual originated when the Israelites smeared sacrificial lamb’s blood over their doors so their homes would be “passed over” and their children spared. Another red line, running vertically from the thick stripe and upward from the highest point of the roof is no less important. These two lines form a cross: one painterly, emotive. The other is exact and painstaking, requiring the viewer’s careful scrutiny. By invoking these rituals and traditions, both Passover and Christ’s Atonement, Wheatley signals performative acts of personal protection and invites us to consider the rich histories of those protections.

Lastly, situated within a biblical lens, the viewer considers the gray cloud hanging over and around the home. Is it a symbol of uncertainty, a natural disaster or global pandemic; or is it the cloud by day, the tent covering the shekinah, leading the Israelites through the wilderness to their home?

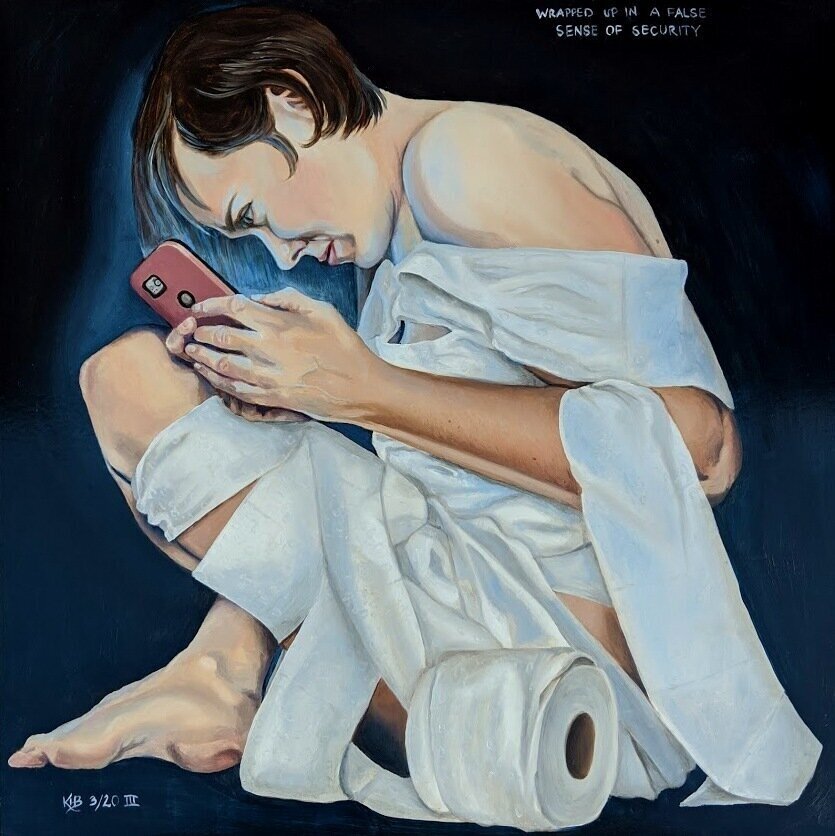

Kirsten Holt Beitler (American, born 1973)

Wrapped Up In A False Sense of Security (2020)

Oil on panel, 19 x 19 inches

Collection of Neva Scott

Kirsten Beitler’s Wrapped Up In A False Sense of Security is immediately familiar. A viewer may recognize themselves in the subject of the painting, finding armor against the unknown by scrolling on their devices or swiping their Costco cards. As an essential employee at a grocery store, Beitler personally witnessed the frenzy of shoppers filling their carts with toilet paper in the early days of the pandemic.

While symbols within Wrapped Up are humorous, ironic, even heavy-handed, the work itself invites further scrutiny into the rich history of vanitas in still life painting. Except that here the subject is part of a static environment. She is isolated, boxed in, and seemingly unaware of her enclosure. In this, Beitler interrogates the elision between escape and escapism. What is the difference between safety and control; and do the tools we use in those circumstances empower or confine us? The subject’s smart phone and toilet paper may feel like armor, but they likewise signal transience and fragility. They are pharmakon, the remedy and the poison. Beitler states, “[The] means of connection is also the thing that can hurt the most…[they] provide little protection against things that can't be controlled.”

Leslie Graff (American, born 1976)

Light Inside (2020)

acrylic on canvas, 30 x 40 inches

Collection of the artist

Few will forget the haunting stillness of New York City during quarantine in the spring of 2020. Evidence of life was quiet, save for our collective cheers shattering through the silence at 7 p.m. each night. The communal celebration of banging pots and pans outside windows to laud first responders became a cathartic ritual.

Leslie Graff’s Light Inside captures the competing sentiments from this time. Early night shadows fall over the anonymous high rise. The setting may remind a New Yorker of home, but the location is unmarked. It is simply urban. The windows are stripped down, allowing the viewer to imagine what shades of living occur inside. Are the lights on? Perhaps young children fill small spaces with pent-up energy, toys, and sounds. Adults power down from their Zoom meetings and defeatedly prepare yet another meal. Or are the lights off? If someone is leaving their apartment, where are they going? Are they sacrificing personal safety to perform essential services like food delivery or medical care, or have they left the city entirely? Perhaps a worse case scenario: The virus has taken a life, shuttering the light. This work is a lyrical display of contrasts, some windows ablaze in color, some in halftones. Even the sky offers rich and saturated variance. Says Graff, “Light has power when it is contrasted with dark.” A “plea for empathy,” Light Inside is an invitation to observe light and dark as typologies, variations on a theme, and to honor all the shades of experience in between.

Grace Poulsen (American, born 1987)

Spring Blossoms Out My Window (2020)

Thrifted fabric, embroidery thread, lace, fabric paint, polyester batting, 12 x 8 inches

Collection of the artist

Grace Poulsen reminds us that things aren’t always what they appear to be. With each stitch of Spring Blossoms, the artist domesticates the terrible into the homespun. Poulsen’s work references graphic virus images that flashed all over news cycles during the early months of the pandemic. These are her hieroglyphs; and she weaves images from the digital imagination into something deeply personal. The artist questions,“The conflict between terrible and beautiful is captivating…like watching someone make the best of a bad situation. We can choose to find good in the bad, or should we?”

There’s something to be said about the work’s form, how the pillow is stitched together. Edges are frayed. Seams are jagged. Images are printed onto the fabric. Spring Blossoms is Poulsen’s reckoning with her “house and her brain and her family” between the months of March and May, 2020. With the collapse of the public and private spheres into quarantines and onto Zoom screens, the texture of existence was changed and life re-patterned. But this project reminds us that while information is domesticated, it’s not always seamless. Spring Blossoms gives form to the discord. And while things may not always be what they appear; if we look closely, the stitches and seams will tell a worthwhile story.

Sue Hansen (American, born 1964)

Saint on a ‘1’ Train (2020)

encaustic collage, 12 x 12 inches

Collection of the artist

The woman in Saint on a 1 Train is both a sister and a stranger. For artist Sue Hansen, Saint is composed of the collection of individuals she encountered while riding the New York City subway. Discarded scraps of paper, even gum wrappers, represent rich stories waiting to be unfolded. The encaustic work deliberately layers scraps to create a larger picture: A woman who is, according to Hansen, “imperfect, complicated, and worthy because she is present.” In fact, the subject’s presence on a train suggests movement; and her delineation as a “saint” indicates her value in the family of God. The woman’s anonymity is significant, however, in that she is any rider, any woman, any scrap of paper that iterates vast and hidden experiences.

In her work, Hansen wrestles with a Latter-day Saint definition of Zion, noted in LDS scripture as God’s kingdom on the earth; a physical location hallmarked by perfect unity and lack of social striation. Saint is a colorful embodiment of Zion. Each layer builds the seemingly raceless, multi-faith woman the same way all peoples form the body of Christ. This work, created just before the Black Lives Matter protests, says something about unity. Hansen describes Zion as a “state free from contention...where no one is spiritually or physically poor, where differences don’t separate us.” Certain markings symbolize this message. The subject’s nimbus borrows from Hansen’s original faith tradition, Catholicism, though the headpiece also references Hindu goddess Devi's crown. A close examination shows the nimbus bearing symbols of the Trinity. As in Justin Wheatley’s work, a red square mark, reminiscent of a ruby and symbolic of the Savior, sits at the northernmost point in the woman’s crown. Two white circles on either side of the red square represent God the Father and the Holy Ghost. Finally, Saint is sealed and protected with encaustic wax. In this, Hansen reminds us that a multiplicity of experiences, faiths, and traditions make up Zion; and that beauty occurs when we are “divinely bound together.”

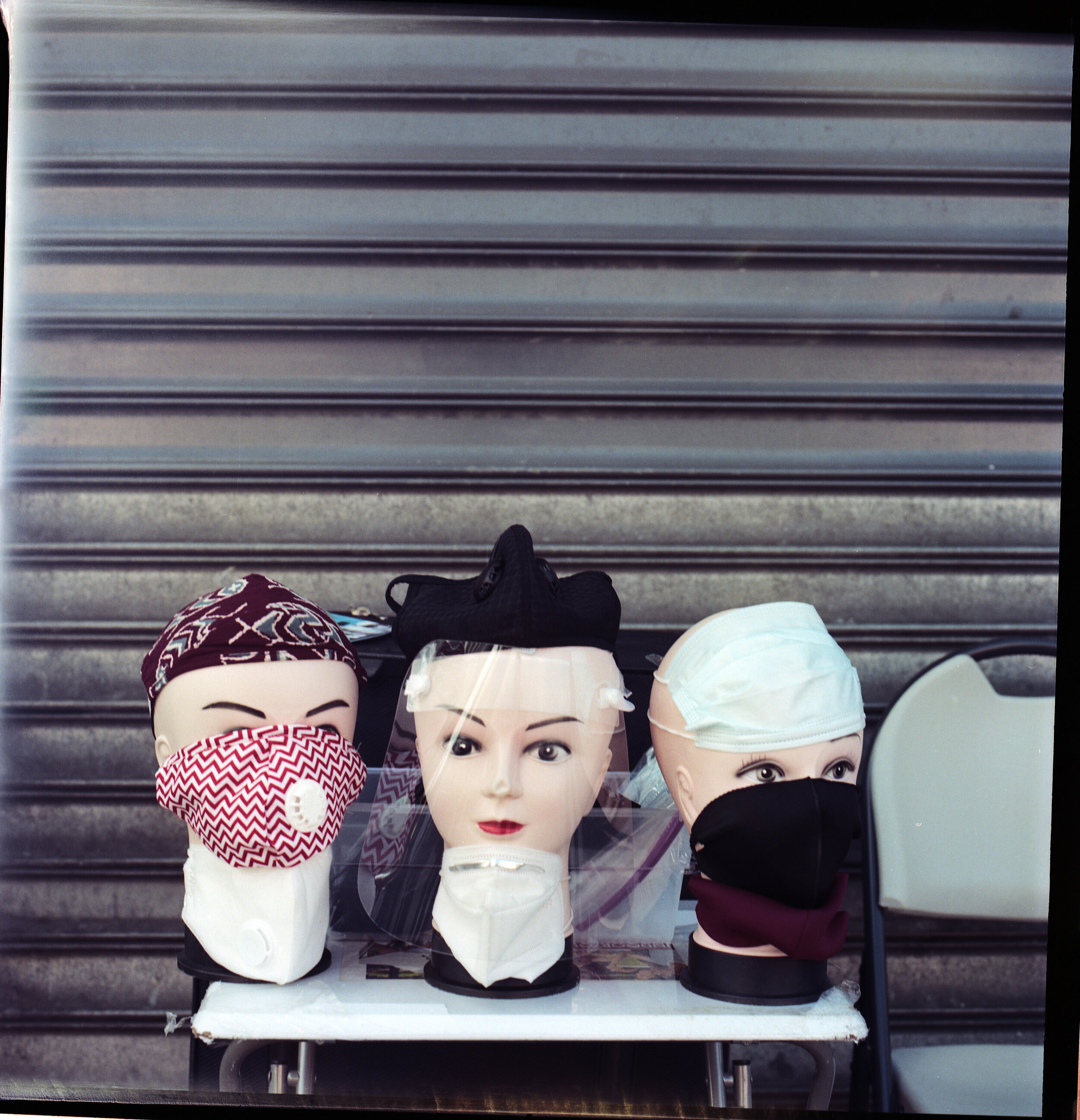

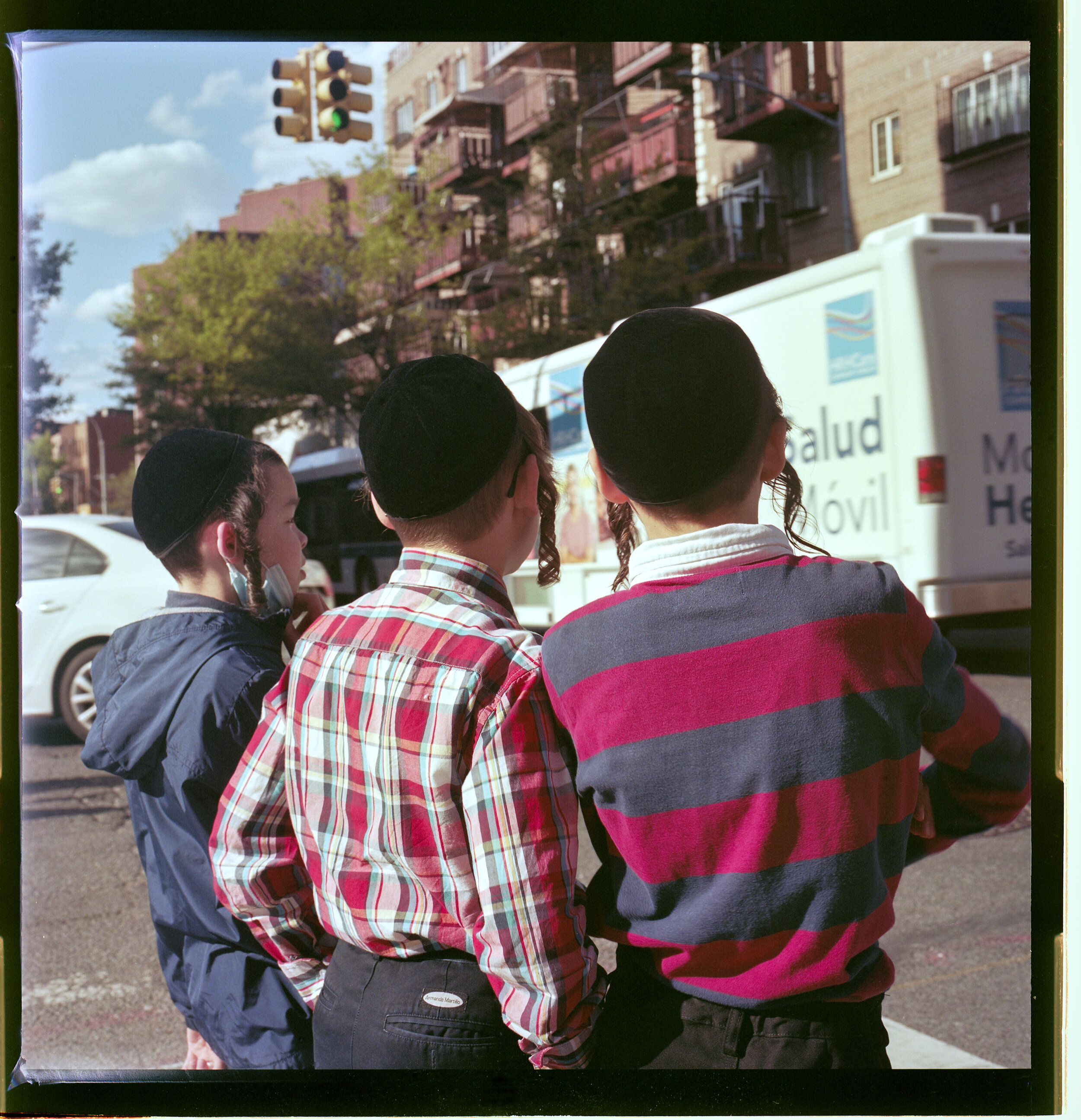

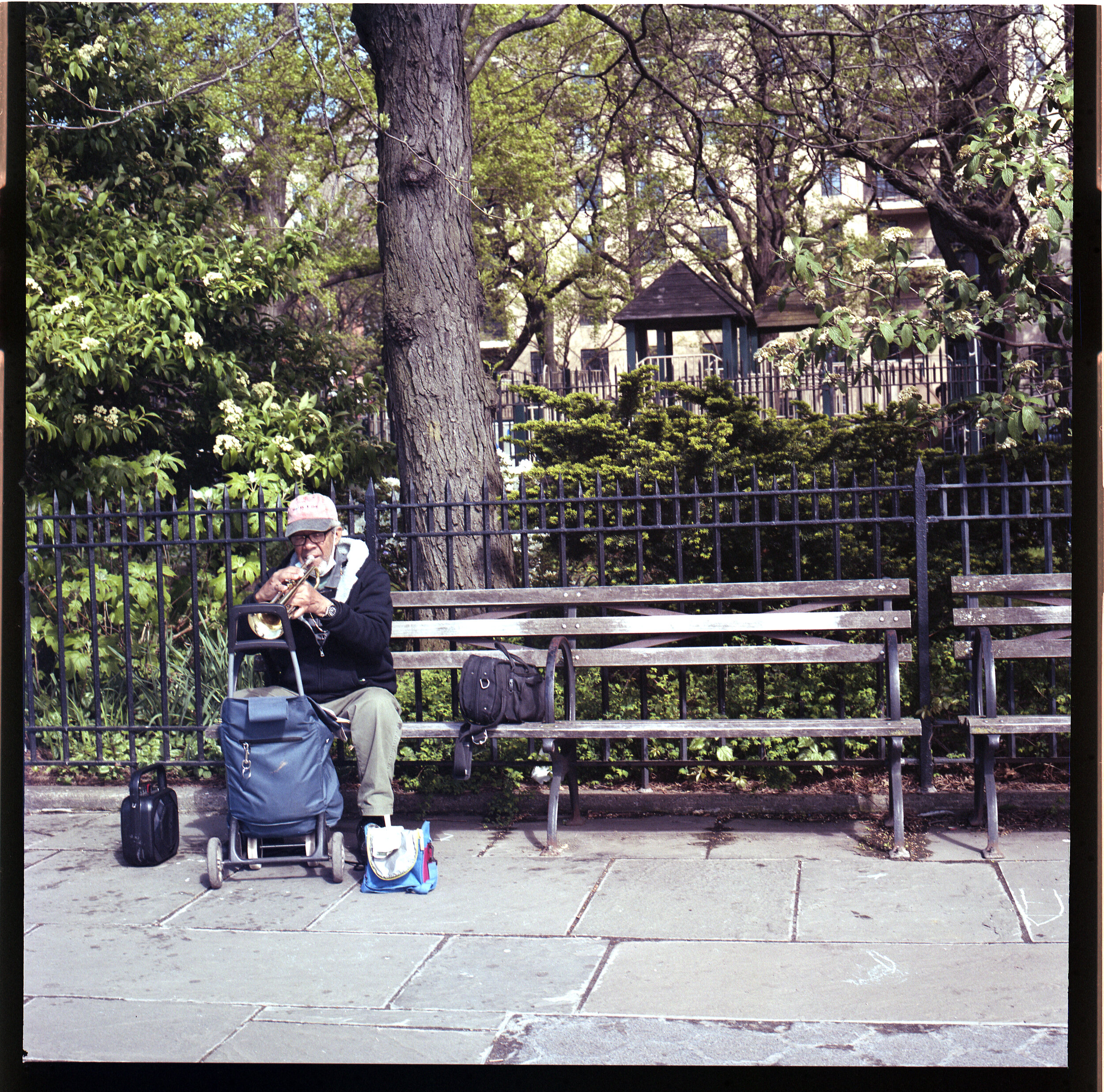

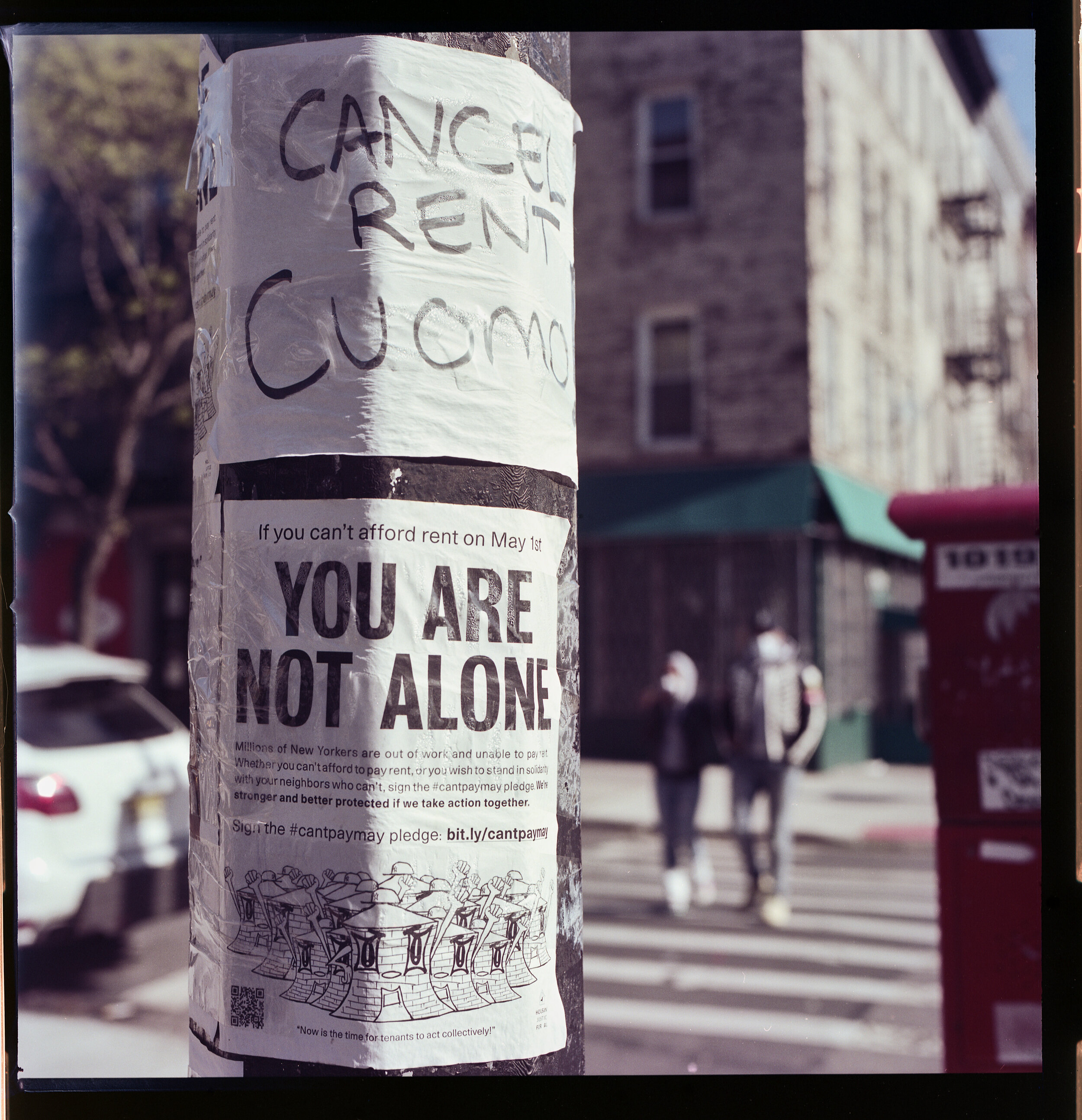

Jeffrey Lee Butler (American, born 1977)

The Lost Months of Brooklyn (2020)

photographs, dimensions variable

Collection of the artist

Jeffrey Lee Butler’s The Lost Months of Brooklyn captures a series of street scenes, photographed during mandated stay-at-home orders, “PAUSE,” in March through May, 2020. The result is both haunting and charming. A desolate stillness pervades the images. Parks are empty, buildings vacated. But moments of intimacy disrupt the isolation: a saxophonist plays sultry tones into vacant streets; young friends huddle together; and street signs remind us, “[we’re] not alone.” A quiet observer, Butler captures people, architecture, and customs and turns their connections upside down.

It’s impossible to view the series without an added lens of retrospect. We observe a wave of social consciousness about to crest, and Lost shows us its tipping point. Because the series returns us to the catalogue of city life just prior to the Black Lives Matter protests last summer, we see a Brooklyn in metamorphosis: Flowers spring from the ground, but parks are empty; friends reconnect, but their smiles are hidden beneath masks. The returns to ritual--Tai Chi, civil protests, even walks in the park--are newly isolated experiences. What will these streets become? The artist captures the unsaid and the unsayable and offers it as an adage. Like a shiny, red Mercedes Benz toy car claimed by a trash pile, he turns what we believed was valuable on its head. Change is afoot.

Maggie Golightly Haslam (American, born 1988)

Bench Friends (2020)

digital print, dimensions variable

Collection of the artist

The cover from Maggie Golightly Haslam’s children’s book Bench Friends showcases her artistic process, which she calls “pour painting.” Devoted to waste-free artmaking, she uses leftover paint and its byproducts, reclaimed discarded matter, and repurposed household goods like fruit and vegetables or published materials to make her own inks and paints. In this work, her loyalty to sustainability underscores her commitment to the natural world, even an urban space like Fort Tryon park in upper Manhattan.

As a children’s book, Bench Friends was decades in the making. The artist’s sister, Eleanor Golightly, wrote its initial draft as a third-grader, years ago. Conceived as a story about two young friends who covertly use a park bench to shuttle notes to one another, never meeting, Haslam was inspired by the pandemic to rewrite the narrative more than a decade later. She placed the characters in Fort Tryon Park during the city’s quarantine and illustrated the story with watercolors. (A copy of the book can be found in the gallery’s book nook, printed by Kah Leong Poon and handbound by Glen Nelson.) Bench Friends invites us to consider how our youngest generation is impacted by COVID-19, and whether small acts of genuine connection can heal a fractured world.

Emily Wall (American, born 1993

Child’s Play (2020)

photograph, dimensions variable

Collection of the artist

Children and caregivers alike recognize this moment of unadulterated joy. Our responses to the image, however, may differ. A caregiver may see Emily Wall’s Child’s Play and remember bending the rules to allow their child to scooter inside their homes during quarantine while a child may remember their newfound freedoms. When the cherished, everyday moments of our existence were stripped from us, improvisation was required.

While psychologists don’t know its lasting impact on our mental health, Wall attempts to capture the silver linings and the moments of joy experienced during the pandemic. She says, “My two young children...do not feel the heightened anxiety of the outside world. Their days still consist of running around, exploring.” She documents fleeting moments of joy to “prove that they exist, that despite my anxieties, despite COVID-19, they happen.”

Adrienne Cardon (American, born 1984)

Afterpains (2020)

Selected poem from And, Still Birth: Death and New Life in a Pandemic

In 2020, poet Adrienne Cardon was 36 years old and expecting her fourth “and final” child. Amidst the global pandemic, health protocols became rigid for expectant mothers, requiring them to bear labor and deliveries alone, masked, and undersupported. During her pregnancy, Cardon made a striking personal discovery when she found the writing of her great-grandmother, Alberta “Bertie” Johnson--also a poet, also 36 years old, also expecting her fourth and final child during a pandemic (the 1918 Spanish influenza). Cardon, like her great-grandmother, turned to poetry to make sense of the world around her. Though they never met in life, she forms a striking written collaboration with her great-grandmother by pairing their texts conversationally in a poem cycle, And, Still Birth: Death and New Life in a Pandemic. This multi-generational witness of women’s perspectives during childbirth is a balm offering for any new parent, helpless and hopeful.

Harriet Petherick Bushman (British, living in Kuwait, born 1953)

Wait on the Lord or the Plaguel Cadence (2020)

video, duration: 3:28

In troubled biblical times, psalms were written and sung for reprieve. Harriet Petherick Bushman’s choral motet is inspired by Psalms, 14, 27, and 57, which asks for prayers and mediation to “keep us safe in the shadow of heavenly wings until calamities pass.” The ancient tradition of a cappella music “relies on the harmonies and the balance of voices for beauty and purity of sound.” This form of communication is poignant during a time when talking heads are everywhere: on the news, our devices, and from various political standpoints. Instead, Bushman shows us where a unity of voices can be seen and heard.

Though the motet--whose title is a play on the musical term “plagal cadence” that offers a harmonic “amen”--doesn’t need to be filmed to face critical muster, Bushman’s Zoom choir made up of singers from Bulgaria, India, England, Scotland, Serbia, Kuwait, Dubai, and the U.S. is a silver lining and a symbol that our world can unite together again.

Sarah Robinson (American, born 1989)

The Signs of the Times (2020)

video, duration: 2:30

As a child growing up in Provo, Utah, Sarah Robinson often heard about the “signs of the times” and “lists of what to watch for and approach with caution.” What were the events she could look for that would help her know the end of the world was imminent? A global pandemic may bring individual faith matters top of mind, but it also begs the question of who else is thinking with you. For Robinson, the project is a contemporary nod to the way faith communities internalize dialogue regarding the signs of the times.

The 10 fifteen-second vignettes in her film almost appear to be still photographs, betrayed by quick, subtle movements of windblown wheat, cars in the distance, signs blowing in the breeze, and foot traffic. These Utah images could depict any number of locations throughout the U.S. last year. Our apocalypse? Not Hollywood’s.

Julian Mansilla (Argentine, born 1981)

...Y la Verdad os Hará Libres (2020)

video, duration: 8:44

S.O.S. On May 24, 1844, Samuel Morse sent Alfred Vail the first message via a telegraph system that would eventually become Morse Code. It was a quotation from Numbers 23:23: “What hath God wrought.” Julian Mansilla builds on the rhythms of this initial message and the technology of Morse Code in the creation of his musical and video work created during the pandemic. The principal instrument, a specialty of the composer from his native Argentina, is the bandoneón, offering a harmonic language on top of the percussive dots and dashes.

A viewer or a listener of ...Y la Verdad os Hará Libres intuits meaning through the coded rhythms.They may not know the beats come from Numbers 23, but they hear it the same way one senses truth without being able to articulate it. Eventually Mansilla’s messages layer on top of one another accumulating into a history of sensory experience.

Keely Song (American, born 1986)

Covenant Keepers (2019)

video, duration: 4:43

In Covenant Keepers, choreographed by Keely Song, the dancers Abby Trinca and Bronte Hopkins have corporeal, almost combative exchanges in seven, recurring locations significant to early Latter-day Saint Church history: Palmyra, New York: Nauvoo, Illinois; Winter Quarters, Iowa; South Pass, Wyoming; Scottsbluff, Nebraska; and Emigration Canyon, Utah. Song states, “The pioneers also faced physical turmoil, economic uncertainty, and emotional difficulties similar to what we endure now. [It] places contemporary women on the physical path of the pioneers.”

Much of Song’s work honors the concept of linkage, or how the challenges and strengths of generational forebears are imprinted into the next generation’s physical body. But with Covenant Keepers, a viewer may find themselves asking the question in the inverse: whether their pandemic trauma, even a struggle with the virus itself, may rewrite an entire genetic code.

Elinor Howard (American, born 2008)

Unease (2020)

photograph, 7.625 x 11.625 inches

Collection of the artist

The next four visual works come from the Art for Uncertain Times: Next Generation call. Unease, a photograph from 12-year-old artist, Elinor Howard, raises the stakes of our viewership. She says, “The eyes are the most expressive part of the face” and this work shows the subject—her father—in a state of fear. In his dilated pupil we see the photographer and two windows behind her.

Howard’s window on the world showcases our own fear—as parents, children, families, and individuals—that can’t be filtered. During a time when our world is collapsed onto flat planes and screens, we may ask: What are we really hiding? And when we encounter such vulnerability, what is our response? Is this a mirror of ourselves?

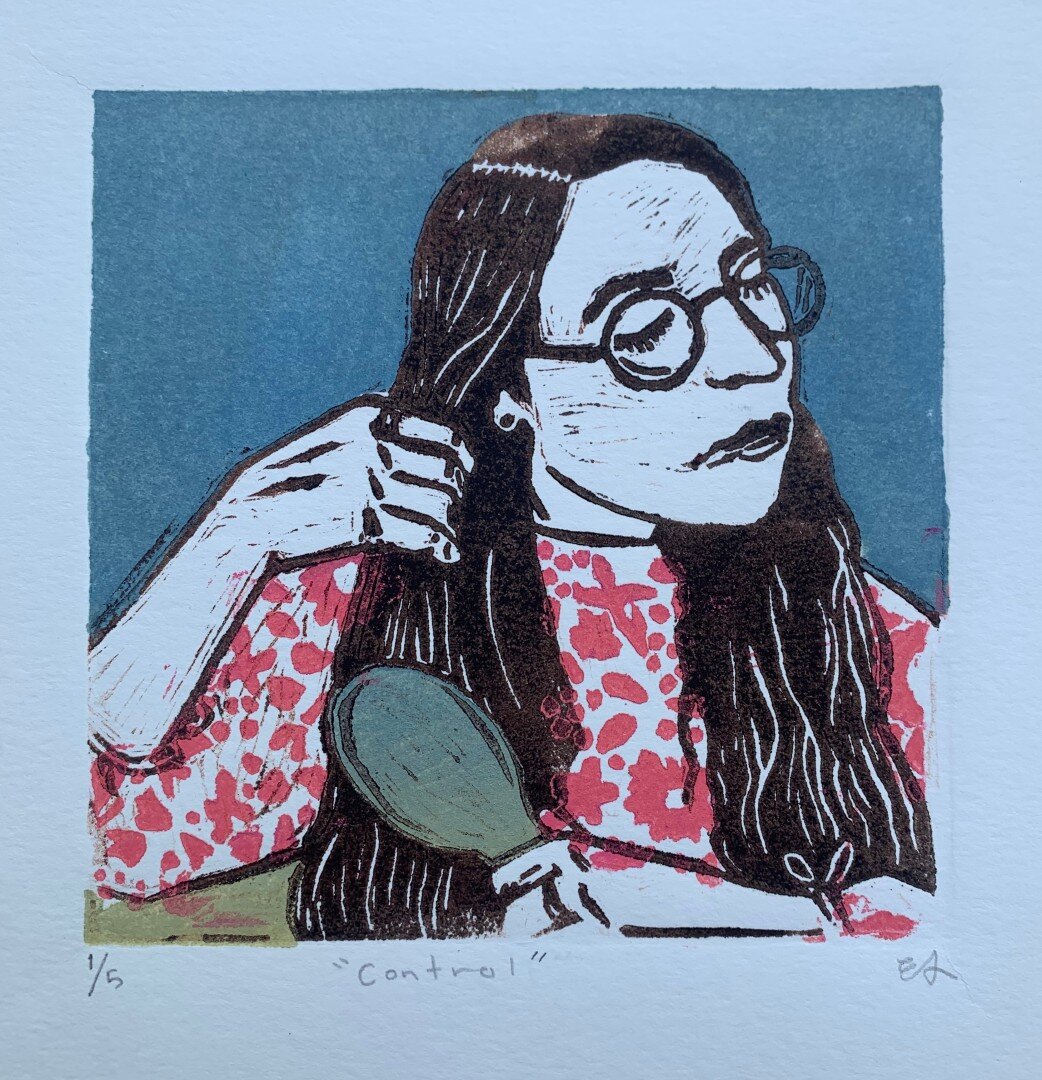

Esther Sanford (American, born 2003)

Control (2020)

block print on paper (2020), 7 x 7.5 inches

Collection of William and Danielle Adams

Esther Sanford, age 18, shares her self-portrait depicting the everyday act of brushing her hair. Only five ink colors appear in the block print: red, blue, green, brown, and sage. The subject, herself, is formed entirely of brown ink. The medium, along with the rough, monochrome lines of her hair and face flatten the image, allowing it to ride the line between realism and caricature; she represents the real and the hyper real, seemingly existing outside the bright patterns and colors around her. This distance is significant. It calls to attention to the red, floral pattern that bleeds into the harsh lines of her hair, an aberration in the block ink process that indicates how much is beyond our control.

Though the self-portrait appears disengaged with the things around her--eyes downcast, looking away from the viewer--the tension in her arms and hands belies her insecurities. Of Control, Sanford says, “When life is out of control like it has been, my ways of coping have turned to very simple everyday things...brushing my hair and going on early morning runs--in these routine things...my heart fills with gratitude for...control over some little things.”

Holden Mack (American, born 2012)

Our Mother in Heaven Heals

oil on canvas, 13 x 25 inches

Collection of the artist

Holden Mack, age 9, is the youngest artist in the exhibition. While Mack is youthful in age, his work shares a history with oils that reference the sacrosanct. The instinct to use bold, painterly strokes isn’t lost on a viewer who may also read feminine shapes amidst the oversaturated, dark colors in the work. It is a war between the feminine and the masculine; hard and soft. About the piece, Mack writes “Covid-19 has ruined and canceled everything. Racism is not ok. I chose to focus my art on Heavenly Mother because I thought that she could help end Covid and racism.”

Diana Yamada (American, born 2005)

Whiteout (2020)

photograph of acrylic on canvas, dimensions variable

Collection of the artist

Next Generation artist, Diana Yamada, age 16, created Whiteout“in response to the Black Lives Matter protests last June.” Her work, a woman of color in protest graffitied on a wall, implicates us. What are we witnessing? Is a layman simply doing his job or is this an act of violence? The man uses white paint to effectively cover over her. But this is more than whitewashing, it is erasure. Thick, painterly stripes cancel her body and redact her mouth, effectively silencing her scream.

Despite her young age, Yamada engages in the dialogue surrounding Critical Race Theory with a single image. The result may be uncomfortable. Although the uniformed painter might simply be doing paid labor to return a wall to an institutional color, we see something nefarious. The subject, a woman of color trapped on a wall, could very well be a Cassandra with prophecies to tell. But who will hear her?

Literature & Other Media

In the book nook of the gallery

Cynthia Austin (American, born 1968)

Jonathan Austin (American, born 1969)

As He Is (2020)

play, 98 pp.

James Best (American, born 1979)

The Last Scenario (2020) (titled subsequently changed to The Last Lake)

play, 13 pp.

Adrienne Cardon (American, born 1984)

Alberta Larsen Jacobs (American, born 1882)

And, Still Birth: Death and New Life in a Pandemic (2020)

book, 64 pp.

Maggie Golightly Haslam (American, born 1988)

Bench Friends (2020)

book, 17 pp.

Printed by Kah Leong Poon and handbound by Glen Nelson

Gabriel González Núñez (American, born 1980)

El Ciclo/ The Cycle (2020)

book, 10 pp., with images from the National Gallery of Art

Farina King (Diné, born 1985)

Diné Doctor: A Latter-day Saint Story of Healing (2020)

essay, 6 pp., with image: Diné Doctor Ashkii Yázhí, by Leah Tiare Smith (King’s niece)

Kindle E-reader

Full archive of dance, literature, music, scholarship, and visual art, scholarship, from the projects: Art for UncertainTimes (2020) and Art for Uncertain Times: Next Generation (2020)

DANCE: Rachel Barker (Salt Lake City, Utah) - Quarantine Book Club: An Energetic Zoom Call; Aubrey Dalley (Orem, Utah) - Untitled; Keely Song (Salt Lake City, Utah) - Covenant Keepers

LITERATURE: Cynthia and Jonathan Austin (Snellville, Georgia) - As He Is; James Best (Brooklyn, New York) - The Last Lake; Adrienne Cardon (Provo, Utah) - And Still, Birth; Maggie Golightly Haslam (New York, New York) - Bench Friends; Gabriel González Núñez (Harlingen, Texas) - El Ciclo/The Cycle

MUSIC: Jed Blodgett/Andrew Maxfield (Windsor Locks, Connecticut/Cambridge, Massachusetts) - Response/ability; Harriet Petherick Bushman (Kuwait City, Kuwait) - Wait on the Lord or The Plague Cadence; Francisco Estévez (Madrid, Spain) - Time for Reflection; Dylan Findley (Kansas City, Missouri) - Music for Earbuds; Daniel E. Gawthrop (Twin Falls, Idaho) - He That Keepeth Thee; Julián Mansilla (Bahía Blanca, Argentina) - Y la Verdad os Hará Libres or ...And the Truth Shall Make You Free; Esther Megargel (American Fork, Utah) - Songs of Comfort and Joy for Soprano, Piano and Flute; Joseph Sowa (Boston, Massachusetts) - Invocation: March 26, 2020; Robert Strobel (Elizabeth, Colorado) - Bearing Us Up; Benjamin Taylor (Bloomington, Indiana) - 6 Feet 6 Degrees

SCHOLARSHIP: Christopher James Blythe (Provo, Utah) - Emma Hale Smith on Stage; Farina King (Tahlequah, Oklahoma) - Diné Doctor: A Latter-day Saint Navajo Story of Healing

VISUAL ART: Kirsten Beitler (Washington, Utah) - Wrapped Up in a False Sense of Security; Paola Bidinelli (Rome, Italy) - Identity and Time; Silvia Borja (Bogota, Colombia) - Fish Out of Water; Laura Lee S. Bradshaw (Sarasota Springs, Utah) - Gleaner; Jeffrey Butler (Brooklyn, New York) - The Lost Months of Brooklyn; Maddison Colvin (Eugene, Oregon) - Threshold (After Sonatine); Lisa Draper (Lehi, Utah) - Break for Hope; Erin Ebert (South Jordan, Utah) - Coming Together on Shaky Ground; Jessica Michelle Ethington (Cedar Park, Texas) - Untitled; Claire Forste (New York, New York) - Sufficient Unto This Day; Jeanne Gomm (Provo, Utah) - Holding Up Excellence; Leslie Graff (Sutton, Massachusetts) - Light Inside; Sue Hansen (Herriman, Utah) - Saint on the 1 Train; Emilie Buck Lewis (Loveland, Colorado) - God Is in the Details; Bekah Meacham (Provo, Utah) - Untitled; Grace Poulsen (Hood River, Oregon) - Spring Blossoms Out My Window; Emma Proudfit (Phoenix, Arizona) - A Conflict of Dreams; Madeline Rands (Sandpoint, Idaho) - Hope; Drew Rane (New York, New York) - Abstract Red (After Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled NRA); Blue Wave I; Blue Wave II; Sarah Robinson (Provo, Utah) - The Signs of the Times; Colby Sanford (Provo, Utah) - What Is Tiny, What Is Big?; Eva Koleva Timothy (Boston, Massachusetts) - The Book of Hours; Emily Wall (East Greenbush, New York) - Child’s Play; Justin Wheatley (Salt Lake City, Utah) - When Dark Clouds of Trouble Hang O’er Us; John Williamson (Lancaster, Pennsylvania) - Walking with Faith and Hope; Nicole Woodbury (Salt Lake City, Utah) - Socially Distant Thoughts

From Art for Uncertain Times: Next Generation

Elementary (4-9)

Anna A. (Troutville, Virginia) - Storm and Sun; Violet G. (Colorado Springs, Colorado) - Rocketship Flying in the Sky; Blake T. (Bloomington, Indiana) - Worship Everywhere; Ezra G. (Colorado Springs, Colorado) - The Canyon; Addison G. (Colorado Springs, Colorado) - Be Careful!; Piper C. (Mesa, Arizona) - Center; Rockwell C. (Mesa, Arizona) - Praising God; Holden M. (Flower Mound, Texas) - Our Mother in Heaven Heals; Ansel M. (Flower Mound, Texas) - A Page from Ansel’s Book

Intermediate (ages 10-14)

Lucy S. (Southlake, Texas) - The Pandemic; Max N. (Spring, Texas) - Onward; Violet O. (New York, New York) - Quarantine; Leah W. (Bellevue, Washington) - Quarantine in Nature; Caylee S. (Garland, Texas) - Alone; Haley E. (Centerville, Utah) - Quarantine; Daniel T. (Bloomington, Indiana) - Hope; Lyndie E. (Centerville, Utah) - Developing Talents; Elinor H. (Orem, Utah) - Unease; Jack T. (Bloomington, Indiana) - Living Outside; Anna B. (Lindon, Utah) - Calm Amidst the Storms of Life; Eleanor M. (Flower Mound, Texas) - After Rain, Always a Rainbow; Magdalene R. (Fountain Hills, Arizona) - The Love of God (The Tree of Life from Lehi’s Vision); Kalynn F. (Fort Worth, Texas) - Trapped

High School (ages 15-19)

Ezra C. (San Diego, California) - Healed in His Arms; Talmage H (Kingwood, Texas) - The Example; Alizabeth O. (Indianola, Iowa) - Overwhelmed; Alba P. (Penhook, Virginia) - Finding Peace; Adalen H. (Kingwood, Texas) - Grounded; Emily Lara H. (Springville, Utah) - Virus Storm; Nefi S. (Fredericksburg, Virginia) - The Staircase; Myra B. (Salt Lake City, Utah) - Loss; Henry G. (New York, New York) - technologic beauty; Tiara O. (Lehi, Utah) - Hope in Color; Emily L. (McKinney, Texas) - Funky Dream Catcher; Hannah B. (Midway, Utah) - Unity; Diana Y. (Scarsdale, New York) - Whiteout; Esther S. (Provo, Utah) - Control; Lynse N. (Democratic Republic of Congo) - Mask; Nathan W. (Orem, Utah) - Invictus; Kapri T. (Sandy, Utah) - Same Colored Tears; Crizo T. (Democratic Republic of the Congo) - My Town